East Jaywick: the most deprived neigbourhood in England. Do people elsewhere care?

Sadly, I live in a world in which we can measure exactly how interested people are in such things.

The answer, too often, is 'not very much'. The answer, too often, is 'I know it's important, but I don't really do the serious stuff'.

In order to identify a solution, we need to be clear about the nature of the problem.

First, the good news: in my experience, it's not that people can't be made to take an interest. It's just that it doesn't always come naturally, at least to most. Not in the way it comes naturally to click on a story about a celebrity doing an ill-advised thing while drunk, or a video of a street brawl, or expert analysis of a football game you just watched.

Second, the not-entirely-surprising news: in general people care more about their own lives than the lives of others, and more about the concrete than the abstract.

To illustrate the point, consider a story that says one in seven women continue to smoke in pregnancy, right up to the moment they give birth.

Will people be interested? To some extent.

But what if the story includes a specific person - a heavily-pregnant woman who gives an interview, and poses for pictures, arguing that she doesn't believe cigarettes are doing her unborn any harm, and in any case she doesn't intend to stop?

That story - the concrete, not the abstract - will get a lot more clicks. It will generate a lot more engagement, and a lot more debate.

And if a reader happens to know the woman in question - the personal, not the general - well, I can't imagine a single person who wouldn't click.

Perhaps that's just human nature. Whatever: there are lessons we can learn, and things data journalism can do to help.

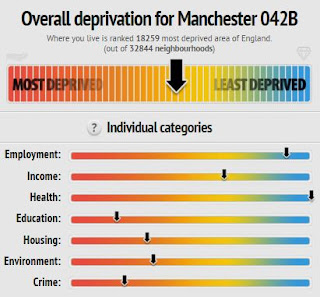

Consider now the recently-published statistics on deprivation in neighbourhoods in England. These were undoubtedly important: they showed that pockets of just a few hundred families in the poorest parts of the country seemed to be trapped at the bottom of the pile, perpetually faring worst, in all respects, than upwardly-mobile places often just a stone's throw away.

Still, unless you lived in one of those neighbourhoods, how much would you actually care?

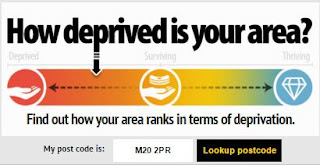

In order to address this - in order to give our coverage a concrete, personal aspect - we created a little gadget which enabled people to enter their postcode and find out exactly how deprived their neighbourhood was (or wasn't).

Hey, presto: a story which had fared quite badly in the past (without a gadget) suddenly became one of the most-read news stories on both the Mirror and the Manchester Evening News. People were sharing their results, talking about their results - and consequently talking about deprivation.

Are these people 'interested' in deprivation in precisely the way that the most noble-minded among us would like? Perhaps not. But they are interested in it.

Maybe they approach it through the prism of their own lives; but if our gadget shows them how lucky they are, and gets them thinking about other people who are far less lucky, I'd say that's more of a win than simply hoping that one day the world will be other than how it is.

No comments:

Post a Comment