Certain certainties

Friday, 7 February 2020

Friday, 23 March 2018

Wednesday, 14 September 2016

The importance of local data

Last week, I found myself in the unusual position of rowing publicly with the Office for National Statistics.

The reason for the row? The ONS had published the annual figures for civil partnerships in England and Wales. Only this year, a bit of the data was missing: the breakdown by local authority.

When I asked when it would be available, I was told it wasn't being published this time.

Now, the reason the row was unusual is that I'm generally a huge fan of the ONS. The Trinity Mirror data unit, which I run, relies heavily on the fact the ONS are so good at publishing fine-grained data, broken down by local authority, or super output area, or whatever. We serve scores of local and regional titles, as well as national ones. One dataset can contain multiple stories for multiple titles.

I don't really want to re-hash the row. Suffice to say the ONS has now published the data, and I'm very grateful for that.

Andy Dickinson, in a very fair summary of the issues, mentioned that some onlookers found the whole issue 'odd', linking to this tweet by James Ball:

While it is true that some ONS data is traditionally issued at national level, or in fairly abstract form, it is pretty much unprecedented for a dataset which has always been published with a local breakdown to suddenly not be published with a local breakdown.

That needs to be resisted, and not just by local or regional journalists. And that's what I want to focus on here: why local data matters, and matters to everyone.

It's fairly obviously true, I think, that local data is more likely to contain information of greater interest to local audiences than national data.

Let's look at that civil partnership data, for instance. Yes, the national figure - civil partnerships falling from 1,683 in 2014 to 861 in 2015, largely because of the availability of same-sex marriage - is interesting to everyone. But if you live in Teesside, you might be more interested to know that there were no civil partnerships at all in your region in 2015. If you live in Brighton, you might be more interested to know there were more civil partnerships there than anywhere else in 2015, and more than in the whole of Yorkshire. If you live in Dorset, you might be more interested to know that your county bucked the national trend, with 11 civil partnerships in 2015 compared to just eight the year before. And if you live in Blaenau Gwent, you might be more interested to know that your area has seen fewer civil partnerships than anywhere else in England or Wales since they first became available, with just 15 in eight years (compared to 1,449 in Brighton).

But it isn't just that local data is more interesting to local audiences. Often the local data contains facts that should be more interesting to everyone.

Take another dataset that came out last week: the number of deaths, related to drugs, in England and Wales. This dataset was broken down by local authority.

Because it was, we were instantly able to see that Blackpool has nearly twice as many drug-deaths per head as anywhere else in Britain.

Just take a moment to consider how astonishing - and alarming - that fact is.

We were also able to plot the rate of drug deaths as a map, which revealed that a remarkable number of the places with the highest incidence of drug-deaths were coastal towns.

When my colleague Patrick Scott (who did the analysis) tweeted this, a number of hypotheses were put forward by readers. Maybe these places also had high deprivation, or unemployment, or a lack of 'fulfilling' jobs or careers. Maybe they were particularly physically (as well as socially) isolated. Maybe it was 'incomers', heading to the coast to party, who were the people doing the dying.

This brings me to the key point about local data. Local data provides the building blocks of analysis. It is where we start if we want to try to understand what is actually going on.

We can, for example, test the theory about drug deaths being correlated with deprivation, since deprivation figures are available at local authority-level, too.

It's only because of that fact that we can plot a graph like this:

Sure, there's some degree of correlation. But there's something else going on in Blackpool. It isn't a simple pattern. There is more to investigate here.

Look, data can be a dangerous thing. A lot of people don't know what they are doing with statistics, and make unwarranted claims. So, sadly, do a lot of journalists - a fact that can make people who do know what they are doing with data reluctant to put it in the hands of those who might not. That, however, is to conflate two separate issues: data literacy (which we need to improve), and data availability (which we need to increase).

Ultimately, the battle is won when more data is available and more people can accurately find patterns, trends and information which are interesting to them. The more local the data, the better the chance it has relevance to our lives, and the better the chance we will be able to use it to make connections that make sense of the world.

Surely that's something worth a little row from time to time?

The reason for the row? The ONS had published the annual figures for civil partnerships in England and Wales. Only this year, a bit of the data was missing: the breakdown by local authority.

When I asked when it would be available, I was told it wasn't being published this time.

Now, the reason the row was unusual is that I'm generally a huge fan of the ONS. The Trinity Mirror data unit, which I run, relies heavily on the fact the ONS are so good at publishing fine-grained data, broken down by local authority, or super output area, or whatever. We serve scores of local and regional titles, as well as national ones. One dataset can contain multiple stories for multiple titles.

I don't really want to re-hash the row. Suffice to say the ONS has now published the data, and I'm very grateful for that.

Andy Dickinson, in a very fair summary of the issues, mentioned that some onlookers found the whole issue 'odd', linking to this tweet by James Ball:

While it is true that some ONS data is traditionally issued at national level, or in fairly abstract form, it is pretty much unprecedented for a dataset which has always been published with a local breakdown to suddenly not be published with a local breakdown.

That needs to be resisted, and not just by local or regional journalists. And that's what I want to focus on here: why local data matters, and matters to everyone.

It's fairly obviously true, I think, that local data is more likely to contain information of greater interest to local audiences than national data.

Let's look at that civil partnership data, for instance. Yes, the national figure - civil partnerships falling from 1,683 in 2014 to 861 in 2015, largely because of the availability of same-sex marriage - is interesting to everyone. But if you live in Teesside, you might be more interested to know that there were no civil partnerships at all in your region in 2015. If you live in Brighton, you might be more interested to know there were more civil partnerships there than anywhere else in 2015, and more than in the whole of Yorkshire. If you live in Dorset, you might be more interested to know that your county bucked the national trend, with 11 civil partnerships in 2015 compared to just eight the year before. And if you live in Blaenau Gwent, you might be more interested to know that your area has seen fewer civil partnerships than anywhere else in England or Wales since they first became available, with just 15 in eight years (compared to 1,449 in Brighton).

But it isn't just that local data is more interesting to local audiences. Often the local data contains facts that should be more interesting to everyone.

Take another dataset that came out last week: the number of deaths, related to drugs, in England and Wales. This dataset was broken down by local authority.

Because it was, we were instantly able to see that Blackpool has nearly twice as many drug-deaths per head as anywhere else in Britain.

Just take a moment to consider how astonishing - and alarming - that fact is.

We were also able to plot the rate of drug deaths as a map, which revealed that a remarkable number of the places with the highest incidence of drug-deaths were coastal towns.

When my colleague Patrick Scott (who did the analysis) tweeted this, a number of hypotheses were put forward by readers. Maybe these places also had high deprivation, or unemployment, or a lack of 'fulfilling' jobs or careers. Maybe they were particularly physically (as well as socially) isolated. Maybe it was 'incomers', heading to the coast to party, who were the people doing the dying.

This brings me to the key point about local data. Local data provides the building blocks of analysis. It is where we start if we want to try to understand what is actually going on.

We can, for example, test the theory about drug deaths being correlated with deprivation, since deprivation figures are available at local authority-level, too.

It's only because of that fact that we can plot a graph like this:

Sure, there's some degree of correlation. But there's something else going on in Blackpool. It isn't a simple pattern. There is more to investigate here.

Look, data can be a dangerous thing. A lot of people don't know what they are doing with statistics, and make unwarranted claims. So, sadly, do a lot of journalists - a fact that can make people who do know what they are doing with data reluctant to put it in the hands of those who might not. That, however, is to conflate two separate issues: data literacy (which we need to improve), and data availability (which we need to increase).

Ultimately, the battle is won when more data is available and more people can accurately find patterns, trends and information which are interesting to them. The more local the data, the better the chance it has relevance to our lives, and the better the chance we will be able to use it to make connections that make sense of the world.

Surely that's something worth a little row from time to time?

Sunday, 22 May 2016

Why that Express splash about '12m Turks' is so mathematically illiterate

"12M TURKS SAY THEY'LL COME TO THE UK," shouted the Sunday Express today. The story was based, they said, on an exclusive opinion poll carried out in Turkey, asking people whether they would want to come to the UK if we stay in the EU, and Turkey joins.

My first thought was: well, that sounds like kind of a lot. Twelve million. The entire population of London and Greater Manchester combined.

My second thought was: I hope they have included a link to the full opinion poll so I can judge the figures for myself.

They did. It is here. And it proves the 12 million figure is utterly unjustified, and the Express has (presumably unwittingly) made some dreadful errors with the statistics.

The 12 million figure is based on a simple calculation. Take the percentage of people who answered 'yes' to the pollsters' question about coming to the UK (15.8%). Apply that to the total population of Turkey (80 million or so). Hey presto, you get about 12 million.

And that's fine.

But let's look at the question that was asked:

Notice the word 'consider'. Not 'would you intend to move', or 'would you probably move', but 'would you consider'. Personally I consider doing a lot of things I'm unlikely to end up doing. I've considered moving to New York. I've considered going vegetarian. When I was buying a car, I considered very many models.

I only ended up buying one.

But the real problem is that other bit: 'or any member of your family'.

This skews the figures completely and renders the 12 million claim utterly null and void.

To understand the point, imagine if Turkey had a population of just 100, neatly divided into 10 separate families.

Now imagine that each of those families had just ONE member who would consider moving to the UK.

It doesn't take a maths genius to realise that the number of people who would consider moving to the UK is 10, and that these 10 make up 10% of the entire population.

But what if we applied Express logic to this group of people?

Let's imagine pollsters choose the first person in each row and ask them the question: "Would you, or any member of your family, consider moving to Britain?"

Now, NONE of the people polled would themselves consider moving to the UK. But ALL of them have a family member who would.

So they would all have to answer 'yes' to the question as put.

We would end up with 10 out of 10 people, 100%, saying 'yes'.

In fact, whichever one of the 100 people you polled, they would all have to say 'yes'. Even though 90% have no intention of even considering moving to the UK.

Applying Express logic, and generalising these figures to the population as a whole, we'd end up with a headline saying that EVERY SINGLE PERSON IN TURKEY was going to come to the UK. And yet clearly only 10 out of 100 were even considering it.

Look at it this way: I imagine as near as dammit 100% of Turks have at least one family member who has considered NOT moving to the UK if Turkey enters the EU. Maybe they are considering moving somewhere else; maybe they are at least considering staying in Turkey.

You wouldn't therefore try to construct a splash saying "ABSOLUTELY NO TURKS WILL ENTER THE UK IF WE MAKE THEM PART OF EUROPE".

That would be equally stupid.

It is, in short, a terrible way to phrase the question if your honest intent is to find out the number of people who are genuinely likely move to the UK in the event of Turkey joining the EU.

(A final note: quite a lot of people on Twitter are criticising the poll for 'only' asking 2,600 people for their opinion. Well, it's a poll. That's how polls work. It's a decent sample size with a tolerable margin of error. There are many things wrong with the poll, but that isn't one of them.)

Sunday, 21 February 2016

How Labour lost Middle England

Ah, Middle England. A mythical place of cafetieres, Scandinavian mini-series and pilates. Where Nissan Qashqais roam the land, carpets are shoe-free zones, and the wine rack is always full of reasonably-priced supermarket reds.

The place - legend has it - where general elections are won or lost.

I grew up in Middle England. At least, I was always pretty sure I had. Detached house in semi-rural Lincolnshire. Went to school at a good local comprehensive. Played cricket and tennis as well as football. That sort of thing.

But perhaps you think you also grew up in Middle England, and perhaps your experience was quite different to mine. That's the problem with Middle England: it's so bloody ill-defined. We all think we know what it is; we just never actually spell it out.

These days it doesn't really matter. We don't need to compare notes from school days, or the labels on our clothes. Demographic data is plentiful, and easy enough to analyse. We can measure the middle of England - and in very precise terms.

Middle England, then, is not a mythical concept at all. It's a mathematical one. Middle England becomes Median England, or Modal England, and there's nothing very mysterious about that.

Let's say Middle England really does decide elections. What did it think in 2015?

First let's get our parliamentary constituencies in some sort of ranked order, from most to least affluent. There are various ways of doing this. For now, let's use a simple measure: house prices, which are available for constituencies here.

Do this, and something immediately becomes apparent: London's housing market is ridiculous and skews the figures dramatically. Nineteen of the 20 constituencies with the highest median house prices in 2014 were in the capital. In Kensington, the average house price was an eye-watering £1.2million.

So we'll leave London out of it.

That leaves us with 460 English constituencies, from Esher and Walton in Surrey (median house price: £465,000) to Liverpool Wavertree (median house price: £78,000).

You'd probably expect the richest areas to vote Conservative. You might not realise the extent to which that happens. In 2015, 34 of the 35 constituencies with the highest median house prices voted Tory.

The one that didn't? Cambridge.

Similarly, 42 of the 43 places with the lowest median house price voted Labour. Pendle, held by the Conservatives' Andrew Stephenson, was the exception.

What, then, of Middle England?

To visualise what happened, let's divide the 460 non-London English constituencies into ten groups of 46. The wealthiest areas, in terms of house price, will be group one. The poorest will be group 10.

Here's what happened at the general election:

What's potentially concerning for Labour here is that even among the seventh group, a majority elected a Conservative MP.

If we take Middle England to be groups 4, 5, 6 and 7, the Tories won 143 seats in Middle England. Labour won 37.

In the old days, of course, Labour didn't really need to win Middle England. It had Scotland, too, where it always did disproportionately well compared to the Conservatives. The SNP wipeout last year had removed that particular crutch. There's no suggestion in the polls it's coming back any time soon.

Labour still does well in Wales, with its 36 MPs, and London, with 54. But if the party doesn't need to win Middle England outright, it certainly needs to be fighting for it.

In 2015, that was a fight Labour lost - and lost badly.

The place - legend has it - where general elections are won or lost.

I grew up in Middle England. At least, I was always pretty sure I had. Detached house in semi-rural Lincolnshire. Went to school at a good local comprehensive. Played cricket and tennis as well as football. That sort of thing.

But perhaps you think you also grew up in Middle England, and perhaps your experience was quite different to mine. That's the problem with Middle England: it's so bloody ill-defined. We all think we know what it is; we just never actually spell it out.

These days it doesn't really matter. We don't need to compare notes from school days, or the labels on our clothes. Demographic data is plentiful, and easy enough to analyse. We can measure the middle of England - and in very precise terms.

Middle England, then, is not a mythical concept at all. It's a mathematical one. Middle England becomes Median England, or Modal England, and there's nothing very mysterious about that.

Let's say Middle England really does decide elections. What did it think in 2015?

First let's get our parliamentary constituencies in some sort of ranked order, from most to least affluent. There are various ways of doing this. For now, let's use a simple measure: house prices, which are available for constituencies here.

Do this, and something immediately becomes apparent: London's housing market is ridiculous and skews the figures dramatically. Nineteen of the 20 constituencies with the highest median house prices in 2014 were in the capital. In Kensington, the average house price was an eye-watering £1.2million.

So we'll leave London out of it.

That leaves us with 460 English constituencies, from Esher and Walton in Surrey (median house price: £465,000) to Liverpool Wavertree (median house price: £78,000).

You'd probably expect the richest areas to vote Conservative. You might not realise the extent to which that happens. In 2015, 34 of the 35 constituencies with the highest median house prices voted Tory.

The one that didn't? Cambridge.

Similarly, 42 of the 43 places with the lowest median house price voted Labour. Pendle, held by the Conservatives' Andrew Stephenson, was the exception.

What, then, of Middle England?

To visualise what happened, let's divide the 460 non-London English constituencies into ten groups of 46. The wealthiest areas, in terms of house price, will be group one. The poorest will be group 10.

Here's what happened at the general election:

What's potentially concerning for Labour here is that even among the seventh group, a majority elected a Conservative MP.

If we take Middle England to be groups 4, 5, 6 and 7, the Tories won 143 seats in Middle England. Labour won 37.

In the old days, of course, Labour didn't really need to win Middle England. It had Scotland, too, where it always did disproportionately well compared to the Conservatives. The SNP wipeout last year had removed that particular crutch. There's no suggestion in the polls it's coming back any time soon.

Labour still does well in Wales, with its 36 MPs, and London, with 54. But if the party doesn't need to win Middle England outright, it certainly needs to be fighting for it.

In 2015, that was a fight Labour lost - and lost badly.

Sunday, 18 October 2015

How to make people care about 'the serious stuff'

I'd love to be able to say I'm an eternal optimist about human nature. I'd love to be able to say that we live in a world of altruistic, concerned, politically-minded people who voraciously seek out stories about public administration, home affairs, economics, and the like, to make sure the world is fair and no one is suffering unnecessarily.

Sadly, I live in a world in which we can measure exactly how interested people are in such things.

The answer, too often, is 'not very much'. The answer, too often, is 'I know it's important, but I don't really do the serious stuff'.

In order to identify a solution, we need to be clear about the nature of the problem.

First, the good news: in my experience, it's not that people can't be made to take an interest. It's just that it doesn't always come naturally, at least to most. Not in the way it comes naturally to click on a story about a celebrity doing an ill-advised thing while drunk, or a video of a street brawl, or expert analysis of a football game you just watched.

Second, the not-entirely-surprising news: in general people care more about their own lives than the lives of others, and more about the concrete than the abstract.

To illustrate the point, consider a story that says one in seven women continue to smoke in pregnancy, right up to the moment they give birth.

Will people be interested? To some extent.

But what if the story includes a specific person - a heavily-pregnant woman who gives an interview, and poses for pictures, arguing that she doesn't believe cigarettes are doing her unborn any harm, and in any case she doesn't intend to stop?

That story - the concrete, not the abstract - will get a lot more clicks. It will generate a lot more engagement, and a lot more debate.

And if a reader happens to know the woman in question - the personal, not the general - well, I can't imagine a single person who wouldn't click.

Perhaps that's just human nature. Whatever: there are lessons we can learn, and things data journalism can do to help.

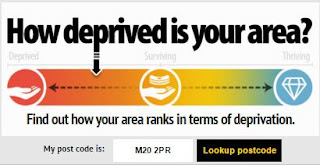

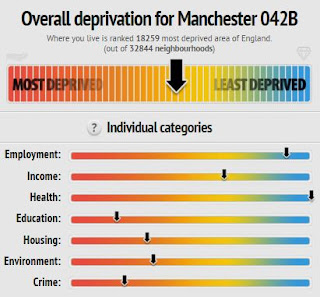

Consider now the recently-published statistics on deprivation in neighbourhoods in England. These were undoubtedly important: they showed that pockets of just a few hundred families in the poorest parts of the country seemed to be trapped at the bottom of the pile, perpetually faring worst, in all respects, than upwardly-mobile places often just a stone's throw away.

Still, unless you lived in one of those neighbourhoods, how much would you actually care?

In order to address this - in order to give our coverage a concrete, personal aspect - we created a little gadget which enabled people to enter their postcode and find out exactly how deprived their neighbourhood was (or wasn't).

Hey, presto: a story which had fared quite badly in the past (without a gadget) suddenly became one of the most-read news stories on both the Mirror and the Manchester Evening News. People were sharing their results, talking about their results - and consequently talking about deprivation.

Are these people 'interested' in deprivation in precisely the way that the most noble-minded among us would like? Perhaps not. But they are interested in it.

Maybe they approach it through the prism of their own lives; but if our gadget shows them how lucky they are, and gets them thinking about other people who are far less lucky, I'd say that's more of a win than simply hoping that one day the world will be other than how it is.

East Jaywick: the most deprived neigbourhood in England. Do people elsewhere care?

Sadly, I live in a world in which we can measure exactly how interested people are in such things.

The answer, too often, is 'not very much'. The answer, too often, is 'I know it's important, but I don't really do the serious stuff'.

In order to identify a solution, we need to be clear about the nature of the problem.

First, the good news: in my experience, it's not that people can't be made to take an interest. It's just that it doesn't always come naturally, at least to most. Not in the way it comes naturally to click on a story about a celebrity doing an ill-advised thing while drunk, or a video of a street brawl, or expert analysis of a football game you just watched.

Second, the not-entirely-surprising news: in general people care more about their own lives than the lives of others, and more about the concrete than the abstract.

To illustrate the point, consider a story that says one in seven women continue to smoke in pregnancy, right up to the moment they give birth.

Will people be interested? To some extent.

But what if the story includes a specific person - a heavily-pregnant woman who gives an interview, and poses for pictures, arguing that she doesn't believe cigarettes are doing her unborn any harm, and in any case she doesn't intend to stop?

That story - the concrete, not the abstract - will get a lot more clicks. It will generate a lot more engagement, and a lot more debate.

And if a reader happens to know the woman in question - the personal, not the general - well, I can't imagine a single person who wouldn't click.

Perhaps that's just human nature. Whatever: there are lessons we can learn, and things data journalism can do to help.

Consider now the recently-published statistics on deprivation in neighbourhoods in England. These were undoubtedly important: they showed that pockets of just a few hundred families in the poorest parts of the country seemed to be trapped at the bottom of the pile, perpetually faring worst, in all respects, than upwardly-mobile places often just a stone's throw away.

Still, unless you lived in one of those neighbourhoods, how much would you actually care?

In order to address this - in order to give our coverage a concrete, personal aspect - we created a little gadget which enabled people to enter their postcode and find out exactly how deprived their neighbourhood was (or wasn't).

Hey, presto: a story which had fared quite badly in the past (without a gadget) suddenly became one of the most-read news stories on both the Mirror and the Manchester Evening News. People were sharing their results, talking about their results - and consequently talking about deprivation.

Are these people 'interested' in deprivation in precisely the way that the most noble-minded among us would like? Perhaps not. But they are interested in it.

Maybe they approach it through the prism of their own lives; but if our gadget shows them how lucky they are, and gets them thinking about other people who are far less lucky, I'd say that's more of a win than simply hoping that one day the world will be other than how it is.

Wednesday, 7 October 2015

Five random post-conference thoughts about politics

1. Jeremy Corbyn's best

hope is to be Jeremy Corbyn

Yes, those on the right

of the party are still pissed off that he won and will leap on him

with glee every time he fails to sing the national anthem, or talks

about nuclear weapons, or wears trousers that don't match his jacket.

So be it.

Jeremy Corbyn's USP is that he isn't part of the political

mainstream, the middle-ground consensus.

Can he win an election from

the left? Almost certainly not. I thought he was a terrible choice for the party and still do. But trying to force him into adopting

a few tokenistic centrist policies, or spending a fortune on spin

doctors to teach him how to walk and talk and dress, will just make him look inauthentic and weak. It would imply

the very thing that made him attractive – his difference, his

idealism – is something he would compromise for a sniff of power.

His only chance is if Britain really has changed as much as the

Labour party. I doubt that very much; but Jeremy Corbyn being Jeremy

Corbyn might at least change the way a few people think about

politics and politicians, stir some passions, frame some important

debates. That matters.

2. Like it or not, David Cameron is a

centrist at heart

It is frankly undeniable that David

Cameron has overseen significant changes in the Conservative party.

Today he got a standing ovation with a passionate plea for religious

tolerance and gender pay-equality. That simply wouldn't have happened

in the pre-Cameron era.

It's easy to forget he won the leadership

election with a positive, eco-friendly, modernising message. It's easy to

believe that lurking behind that message, always, was a true-blue

Thatcherite heart.

And yet, however strategically sensible it might

have been for him to pitch for the centre ground today, he didn't

have to. He has a majority. He is planning to stand down. He

can do what he wants for the next four years.

What he wants to do, I

suspect, is define his legacy. And he wants that legacy to be as a

leader of Britain, not a leader of the Conservatives.

3. Ed Miliband was a

disaster for Labour

Put simply, the party has learned the wrong

lessons from his defeat.

Ed Miliband didn't lose because of the

media. He didn't lose because he was too left wing, or too right

wing. And he didn't lose because he wasn't 'authentic'.

In fact, he

was: authentically Ed Miliband. A well-meaning, nice-enough, slightly

geeky, Islington socialist. A man who had never lived, and didn't

understand, the lives of the very 'hard-working families' he talked

about so much.

He never really spoke about schools and education. He

didn't recognise how much people might want to own their own homes.

Instead he focused on the extremes: the very poor and the very rich.

While plenty of people trying to raise a family on the median wage

(or just below) might think the 'bedroom tax' led to some unfair

outcomes, or that the very rich should contribute more in tax, these

really aren't their main concerns.

That doesn't make them awful

people. Ed Miliband had no intuitive understanding of those concerns.

So they didn't vote for him.

4. Politics is getting

more divisive

Win or lose, Jeremy

Corbyn has already achieved one thing: he has stirred and emboldened

those people on the left who might have thought 'mainstream' politics

deserted them during the Blair years.

The tens of thousands

who marched through Manchester this weekend did so in the belief, the

knowledge, that through the new Labour leadership they are now part

of the debate. Or rather, that their voice will now be heard. Whether

they are interested in listening is another matter.

Either way, the

ranks of the 'noisy disenchanted' will swell; anger will drive more

of the discourse; and it is hard to predict quite how that will

end. It's very easy for older hacks to claim that this is simply the

1980s all over again. But a glance over the border to Scotland should

show just how quickly politics can change in

remarkable ways.

5. The Liberal Democrats

are in serious trouble

The Liberal Democrat

conference seemed to pass by almost unremarked. You'd think Labour

vacating the central ground would present them with a real

opportunity. But no one appears to be talking about the Lib Dems.

That's bad. At least former Lib Dem voters felt something

about Nick Clegg, even if it was anger. Now it seems like a lot of

people don't feel anything about the Lib Dems at all.

Tim Farron is

going to have to work extremely hard simply to get a hearing. Cameron pitching for the centre ground will make things even worse.

It's

actually quite sad, in a way, to see a party which worked so hard to

get a footing – particularly in local government – have to

essentially start again from scratch.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)